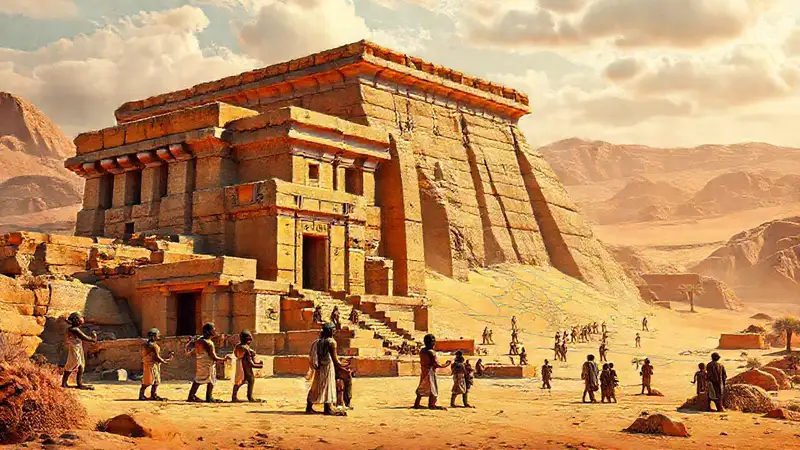

Ancient Nubia, located south of Egypt along the Nile River, enjoyed a remarkably complex and influential history. For centuries, it served as a crucial source of resources for the Egyptians, supplying them with gold, ivory, ebony, and exotic animals. However, Nubia’s own civilization was sophisticated and independent, developing its own unique cultural, religious, and architectural traditions. This dynamic relationship, built upon extensive trade, eventually fueled a fascinating exchange of ideas and styles, most notably in the construction of monumental tombs – the pyramids. Understanding the pyramids of Nubia is essential to appreciating the scope of Nubian power and religious beliefs.

The pyramids of Nubia, often overshadowed by their Egyptian counterparts, offer a compelling window into a distinctly Nubian identity. While heavily influenced by Egyptian models, they represent a unique adaptation and evolution of royal burial practices. Moreover, their location – often strategically situated along vital trade arteries – reveals a deliberate attempt to solidify political control and project an image of power throughout the region. Deciphering their purpose and comparing them to the nearby Egyptian pyramid sites reveals a deeper understanding of this complex ancient civilization.

The Egyptian Influence on Nubian Pyramids

The roots of Nubian pyramid construction are undeniably intertwined with Egypt. Beginning in the 9th century BC, the Kingdom of Kush, a Nubian state, adopted Egyptian customs and architectural styles, beginning with the replication of the Egyptian pyramid design. Initially, these Nubian pyramids were essentially copies of the Egyptian structures, built with similar materials and utilizing similar construction techniques, though often on a smaller scale. Kushite rulers, particularly those of the 25th Dynasty, sought to legitimize their rule by associating themselves with the powerful and prestigious traditions of Egypt.

This imitation wasn’t merely superficial; it reflected a genuine desire to emulate Egyptian authority and demonstrate a commitment to Egyptian religious beliefs. The architects and engineers of Kush employed Egyptian supervisors and utilized Egyptian quarrying methods, highlighting the reliance on Egyptian expertise. The sheer number of Egyptian-style pyramids erected in the early Kushite period demonstrates a concerted effort to establish a clear line of succession and demonstrate royal legitimacy through mirroring Egyptian precedents, showcasing the powerful impact of the Egyptian empire on the nascent Nubian kingdom. The reliance on Egyptian craftspeople also fostered a vibrant exchange of knowledge.

However, even within this adoption, subtle differences began to emerge. The orientation of some pyramids, for example, deviated slightly from the purely solar-aligned principles of the Egyptians, and the quality and materials used often showed a preference for local Nubian stone, suggesting a gradual assertion of distinct Nubian identity. This initial phase was a critical period of cultural adaptation, laying the groundwork for the development of a genuinely Nubian architectural style.

Size and Scale: A Nubian Counterpoint

While the initial Nubian pyramids were smaller and less elaborate than their Egyptian predecessors, they steadily grew in size over time. The 25th Dynasty witnessed a significant increase in scale, with pyramids reaching heights comparable to those of the Old Kingdom Egyptians. This shift reflects a growing confidence and wealth within the Kushite kingdom, indicating a rising power and the ability to invest in monumental construction.

Despite these advancements, the Nubian pyramids remained generally shorter and steeper than those of the Old Kingdom Egyptians. This difference is often attributed to variations in the quality of the stone and the local construction techniques. Nubian quarries were frequently located closer to the building sites, leading to a more efficient, though perhaps less refined, process. Furthermore, the shape and slope of the pyramids were often more rounded and less sharply angled, a subtle but noticeable stylistic difference.

The reduced scale, coupled with the altered angles, highlights a deliberate divergence from the Egyptian model. It wasn't about simply replicating; it was about demonstrating Nubian control over the building process, using local resources and adapting the design to suit the Nubian landscape and capabilities. The size of the pyramids ultimately became a symbol of the Kushite ruler's strength and prestige, comparable to the pyramids of Egypt.

Location and Trade Routes

The strategic placement of Nubian pyramids is perhaps their most striking feature. Many were situated along major trade routes that connected Nubia with Egypt, Sudan, and the wider Mediterranean world. These locations were not chosen at random; they reflected the kingdom's role as a vital intermediary in the exchange of goods and ideas. The pyramids served as visible markers of Kushite authority and control over these crucial pathways.

Furthermore, the proximity to these trade routes ensured that the pyramids were frequently visited by foreign dignitaries, merchants, and emissaries. This constant interaction exposed the Kushite rulers to new ideas and technologies, further enriching their culture and influencing their architectural practices. Sites like Nuri and Meroë, surrounded by vast trading networks, became centers of royal power and served as impressive statements of Nubian economic and political dominance.

The location itself acted as a constant reminder of Nubia's importance in the regional and international economy, solidifying its position as a crucial link in the ancient world’s network of commerce. The pyramids themselves, built on these vital routes, were therefore integral to the functioning of the kingdom’s trade.

Religious Significance and Royal Ideology

While influenced by Egyptian religious concepts, the Nubian pyramids developed their own unique religious significance. Unlike the Egyptian pharaohs who were viewed as divine rulers, the Kushite kings adopted a more complex blend of Egyptian and Nubian religious beliefs. The pyramids were not just tombs; they were also considered sacred spaces, imbued with power and associated with the royal lineage.

The internal chambers and passages of the pyramids were decorated with intricate relief carvings depicting scenes of religious rituals, royal processions, and mythological narratives. These scenes often incorporated both Egyptian and Nubian deities, reflecting the kingdom's syncretic religious practices. The emphasis on lineage and royal succession was paramount, reinforcing the divine right to rule and maintaining the stability of the kingdom.

Crucially, the pyramids served as a tangible representation of the Kushite ruler’s connection to the gods and their ancestors. Their construction was a profoundly religious act, intended to ensure the king's successful transition into the afterlife and to perpetuate the royal line for generations to come. This blending of Egyptian and Nubian religious thought created a distinctly Nubian royal ideology centered on the pyramids as a cornerstone of their power and legacy.

Conclusion

The pyramids of ancient Nubia represent a fascinating chapter in the history of ancient architecture and religious belief. They stand as a testament to the enduring legacy of Egyptian influence combined with the distinct Nubian response, resulting in a truly unique architectural style. Their evolution over centuries, from near-perfect copies of Egyptian models to increasingly independent structures, showcases a complex and dynamic relationship between the two civilizations.

Ultimately, the Nubian pyramids, situated strategically along vital trade routes and imbued with potent religious symbolism, reveal a kingdom that successfully forged its own path – one that blended the grandeur of Egyptian tradition with the resourcefulness and identity of ancient Nubia. Studying these monumental tombs provides invaluable insight into the history, religion, and political power of this often-overlooked but significant ancient civilization.

How did Nubian pyramids relate to neighboring cultures

How did Nubian pyramids relate to neighboring cultures What are some examples of logographic systems

What are some examples of logographic systems What ongoing projects are furthering pyramid research

What ongoing projects are furthering pyramid research What architectural innovations defined Nubian pyramids

What architectural innovations defined Nubian pyramids How are researchers deciphering pyramid inscriptions

How are researchers deciphering pyramid inscriptions Analyze the Kushite relationship with neighboring African groups

Analyze the Kushite relationship with neighboring African groups What architectural innovations did Kush inherit from Egypt

What architectural innovations did Kush inherit from Egypt How did Kushite scribes maintain administrative records

How did Kushite scribes maintain administrative records

Deja una respuesta